Pyszczkowiak atlantycki

| Oxymycterus dasytrichos[1] | |||

| (Schinz, 1821) | |||

| Systematyka | |||

| Domena | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Królestwo | |||

| Typ | |||

| Podtyp | |||

| Gromada | |||

| Podgromada | |||

| Infragromada | |||

| Rząd | |||

| Podrząd | |||

| Infrarząd | |||

| Nadrodzina | |||

| Rodzina | |||

| Podrodzina | |||

| Plemię | |||

| Rodzaj | |||

| Gatunek |

pyszczkowiak atlantycki | ||

| Synonimy | |||

| |||

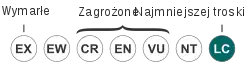

| Kategoria zagrożenia (CKGZ)[11] | |||

| |||

Pyszczkowiak atlantycki[12], pyszczkowiak kanciasty[12], pyszczkowiak kosmaty[12], pyszczkowiak araukariowy[12] (Oxymycterus dasytrichos) – gatunek ssaka z podrodziny bawełniaków (Sigmodontinae) w obrębie rodziny chomikowatych (Cricetidae).

Zasięg występowania

Pyszczkowiak atlantycki występuje we wschodniej Brazylii (Alagoas, Ceará i Pernambuco)[13][14][11][15].

Taksonomia

Gatunek po raz pierwszy zgodnie z zasadami nazewnictwa binominalnego opisał w 1821 roku szwajcarski lekarz i przyrodnik Heinrich Rudolf Schinz nadając mu nazwę Mus dasytrichus[2]. Holotyp pochodził z dolnego biegu rzeki Mucuri, w stanie Bahia, w Brazylii[15].

Powszechnie stosowana nazwa gatunkowa dasytrichus jest nieuzasadnioną poprawką oryginalnej nazwy dosytrichos[13]. Obecna koncepcja taksonomiczna O. dosytrichos obejmuje taksony rostellatus, hispidus, roberti i angularis[13]. Autorzy Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World uznają ten takson za gatunek monotypowy[13].

Etymologia

Morfologia

Długość ciała (bez ogona) 125–197 mm, długość ogona 90–156 mm, długość ucha 18–26 mm, długość tylnej stopy 30–42 mm; masa ciała 40–105 g[14].

Ekologia

Zamieszkuje tropikalny, suchy scrub oraz otwarte obszary[11]. Zwierzę lądowe[11].

Status i zagrożenia

Ze względu na rozpowszechnienie i populację IUCN oceniło go na najmniejszej troski[11]. Gatunek ten nie ma większych zagrożeń[11].

Uwagi

Przypisy

- ↑ Oxymycterus dasytrichos, [w:] Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ang.).

- 1 2 H.R. Schinz: Das Thierreich, eingetheilt nach dem Bau der Thiere als Grundlage ihrer Naturgeschichte und der vergleichenden Anatomie von den Herrn Ritter von Cuvier. Cz. 1: Säugethiere und Vögel. Stuttgart und Tübingen: in der J.G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, 1821, s. 288. (niem.).

- ↑ M. zu Wied-Neuwied: Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte von Brasilien. Weimar: Im Verlage des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1825, s. 425. (niem.).

- ↑ J.A. Wagner. Diagnosen neuer Arten brasilischer Säugthiere. „Archiv für Naturgeschichte”. 8 (1), s. 361, 1842. (niem.).

- ↑ F.-J. Pictet. Description de l’Oxymycterus hispidus. „Memoires de la Société de physique et d’histoire naturelle de Genève”. 10 (1–2), s. 212, 1843. (ang.).

- ↑ H.R. Schinz: Systematisches Verzeichniss aller bis jetzt bekannten Säugethiere oder Synopsis Mammalium nach dem Cuvier’schen System. Cz. 2. Solothurn: Verlag von Jent und Bakmann, 1845, s. 179. (niem.).

- ↑ É.L. Trouessart: Catalogus mammalium tam viventium quam fossilium. Wyd. Nova ed. (prima completa). Cz. 1: Primates, Prosimiae, Chiroptera, Insectivora. Berolini: R. Friedländer & sohn, 1897, s. 539. (łac.).

- ↑ O. Thomas. On mammals obtained by Mr. Alphonse Robert on the Rio Jordäo, S. W. Minas Geraes. „The Annals and Magazine of Natural History”. Seventh series. 8, s. 530, 1901. (ang.).

- ↑ O. Thomas. Notes on some South-American mammals, with descriptions of new species. „The Annals and Magazine of Natural History”. Eight series. 4, s. 237, 1909. (ang.).

- ↑ G.H.H. Tate. The taxonomic history of the South and Central American akodont rodent genera: Thalpomys, Deltamys, Thaptomys, Hypsimys, Bolomys, Chroeomys, Abrothrix, Scotinomys, Akodon, (Chalcomys and Akodon), Microxus, Podoxymys, Lenoxus, Oxymycterus, Notiomys, and Blarinomys. „American Museum novitates”. 582, s. 17, 1932. (ang.).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 C.R. Bonvicino, Oxymycterus dasytrichus, [w:] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016, wersja 2021-3 [dostęp 2021-12-19] (ang.).

- 1 2 3 4 W. Cichocki, A. Ważna, J. Cichocki, E. Rajska-Jurgiel, A. Jasiński & W. Bogdanowicz: Polskie nazewnictwo ssaków świata. Warszawa: Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, 2015, s. 253. ISBN 978-83-88147-15-9. (pol. • ang.).

- 1 2 3 4 C.J. Burgin, D.E. Wilson, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, T.E. Lacher & W. Sechrest: Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 1: Monotremata to Rodentia. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2020, s. 412. ISBN 978-84-16728-34-3. (ang.).

- 1 2 U. Pardiñas, P. Myers, L. León-Paniagua, N.O. Garza, J. Cook, B. Kryštufek, R. Haslauer, R. Bradley, G. Shenbrot & J. Patton. Opisy gatunków Cricetidae: U. Pardiñas, D. Ruelas, J. Brito, L. Bradley, R. Bradley, N.O. Garza, B. Kryštufek, J. Cook, E.C. Soto, J. Salazar-Bravo, G. Shenbrot, E. Chiquito, A. Percequillo, J. Prado, R. Haslauer, J. Patton & L. León-Paniagua: Family Cricetidae (True Hamsters, Voles, Lemmings and New World Rats and Mice). W: D.E. Wilson, R.A. Mittermeier & T.E. Lacher (redaktorzy): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Cz. 7: Rodents II. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2017, s. 464. ISBN 978-84-16728-04-6. (ang.).

- 1 2 D.E. Wilson & D.M. Reeder (redaktorzy): Species Oxymycterus dasytrichus. [w:] Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (Wyd. 3) [on-line]. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. [dostęp 2020-12-02].

- ↑ T.S. Palmer. Index Generum Mammalium: a List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. „North American Fauna”. 23, s. 491, 1904. (ang.).

- ↑ Jaeger 1944 ↓, s. 68.

- ↑ Jaeger 1944 ↓, s. 236.

Bibliografia

- Edmund C. Jaeger, Source-book of biological names and terms, wyd. 1, Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1944, s. 1-256, OCLC 637083062 (ang.).